1980-2022: Climate Change Impacts Corn Seed Production

How will climate change impact corn seed production in the coming decades? To answer this question, in 2022, the FNPSMS launched a comprehensive study identifying risks, the most vulnerable stages of corn, and the resilience abilities of the crop. One first step in that process was to take a look back at the crop’s development over the past forty years.

The FNPSMS placed the topic of climate change resilience at the heart of its “Actions Techniques Semences” programme, which focuses on technical work regarding seed. Under this programme, in 2022, the FNPSMS launched an extensive study, carried out by the Arvalis Institute, to measure the frequency and geographic impact of climatic factors on the physiology and production abilities of corn seed parent lines. The first stage of the study consisted in collecting data covering the past forty years, dividing them into two parts: those belonging to a more distant past, going from 1983 to 2002, and to a recent one, between 2003 and 2022.

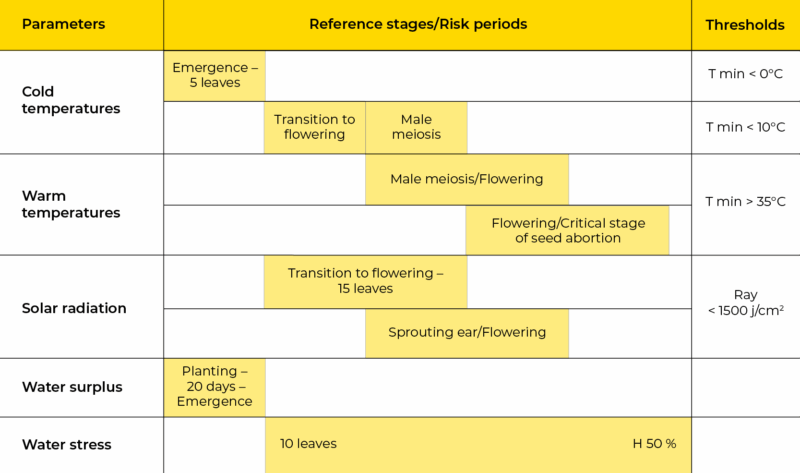

“This first exercise was aimed at listing the dates of the key growth stages in corn, every year and at each location (seventeen in all), based on typical agronomic cases, especially in terms of planting dates and earliness”, Régis Doucet, expert with the Arvalis-Institut du végétal, explains. Then weather hazards were associated (along with critical thresholds – extreme hot/cold temperatures; improper solar radiation; water deficit/surplus) at each vulnerable physiological stage: emergence, male meiosis, flowering…. All this was done in order to ensure an ecoclimatic approach. The objective of the study is not to quantify the impact on the yield, but to understand how the formation of a specific component of the yield (such as pollen production or ear development) may be impacted – so that one may eventually adapt the production itinerary of the crop. We are therefore very focused on the two – male and female – parent lines.”

Weather parameters, intervals of concern, and thresholds taken into account in the study

(Source: Study on the impact of climate change and the resilience of seed corn crops)

Growing Risk of Drought Years

Observations made over the past four decades have indicated that the risk of spring frost during the 5-leaf emergence stage can lead to plant losses or to significant delays in crop growth. Also, during the transition towards the flowering stage, if temperatures drop below 10°C, one may see tillering flaws, blocked flowering or early ear abortions. Conversely, excessive temperatures (above 35°C) will lead to growth flaws between male meiosis and flowering and may cause pollen viability losses in later stages.

“In other words, the temperature trends recorded over the past forty years have already had a concrete impact upon the crops’ growth cycles”, he says. “The risk of temperatures rising above the 35°C threshold has increased over the past two decades”. As to the cold and solar radiation, they indicate “a rather net attenuation of risks, when we compare the current norm to the previous twenty years”. In terms of the water excess/deficit risk, facts indicate that the total amounts of rainfall in specific areas have made little progress, but it is their distribution throughout the crop growth that has changed. Thus, the crop’s period of vulnerability to water stress has moved to an earlier point in the season. The risk of stress has not changed much on average, but we notice years characterized by unusual drought risks, such as 2003 and 2022.

Avoidance Techniques, Already in Place

How do such techniques affect seed production? Several types of avoidance methods have already been put to work. At similar planting dates and earliness levels, the temperature rise causes a shortening of the average length of the growth cycles. “The phenomenon is barely noticeable during the first part of the cycle, but it becomes significant at the flowering stage and even more at the time of physiological maturity” – Régis Doucet points out. On average, in all regions covered by the study, the flowering stage occurs 4.7 days earlier and last somewhere between three to six days. “This retrospective study has helped us to think about the ways in which we can adjust the crops’ production itineraries in the coming decades, starting with the shifting of the planting dates, in order to prevent the more vulnerable stages from overlapping with high-risk intervals. This is a route that people have already embarked upon, since on average, plantings have taken place a day earlier once every three years, over the past twenty years. This finding must of course be included in the prospective studies that we are carrying out at present”, he concludes.